|

●★ Ludwig van Beethoven Sonata in c Op.111「A r i e t t a」★●

Maestoso - Allegro conbrio ed Appassionato Arietta : Adagio molto semplice e Cantabile

Performed by Wilhelm Backaus

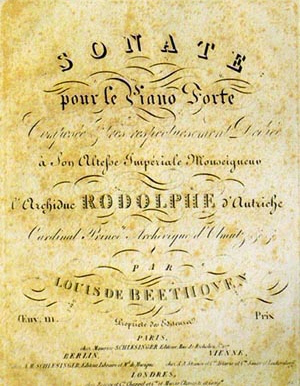

● Piano Sonata No.32 in c Op.111The Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111, is the last of Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonatas. Along with Beethoven's 33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120 (1823) and his two collections of bagatelles—Opus 119 (1822) and Opus 126 (1824)—this was one of Beethoven's last compositions for piano. The work was written between 1821 and 1822. Like other "late period" sonatas, it contains fugal elements.

● StructureThe work is in two highly contrasting movements:

Typical performances take 8 to 9 minutes for the first movement, and 15 to 18 minutes for the second. The first movement, like many other works by Beethoven in C minor (see Beethoven and C minor), is stormy and impassioned. It abounds in diminished seventh chords, as in for instance the first full bar of its opening introduction:

The final movement, in C major, is a set of variations on a 16-bar theme, with a brief modulating interlude and final coda. The last two are famous for introducing small notes which constantly divide the bar in 36 resp. 27 parts, which is very uncommon. Beethoven eventually introduces a trill which gives the impression of a further step (i.e. dividing each bar into 81 parts), though this is extremely technically difficult without slowing down to half-tempo. Beethoven’s markings indicate that he wished variations 2-4 to be played to the same basic pulse as the theme, first variation and subsequent sections (using the direction "L'istesso tempo" at each change of time signature).[1] However, performance practice today often makes the theme and first variation slow, with wide spaces between the chords, and lets the third variation, which has a powerful, stomping, dance-like character with falling 32-part notes, come out much faster and with heavy syncopation. Mitsuko Uchida has remarked that this variation, to a modern ear, has a striking resemblance to cheerful boogie-woogie,[2] and the closeness of it to jazz and ragtime, which were still eighty years into the future at the time, has often been pointed out. Jeremy Denk, for example, describes the second movement using terms like "proto-jazz" and "boogie-woogie".[3] The work is one of the most famous compositions of the composer's "late period" and is widely performed and recorded. The pianist Robert Taub has called it "a work of unmatched drama and transcendence ... the triumph of order over chaos, of optimism over anguish."[4] Alfred Brendel commented of the second movement that "what is to be expressed here is distilled experience" and "perhaps nowhere else in piano literature does mystical experience feel so immediately close at hand".[5] Asked by Anton Schindler why the work has only two movements (this was unusual for a classical sonata but not unique among Beethoven's works for piano), the composer is said to have replied "I didn't have the time to write a third movement." However, according to Robert Greenberg, this may have just as easily been the composer's prickly personality shining through, since the balance between the two movements is such that it obviates the need for a third.[6] Jeremy Denk points out that Beethoven "whittles away everything down to the absolute difference of the two movements", "an Allegro and an Adagio, two opposed poles", and suggests that "as with the greatest Beethoven pieces, the structure itself becomes a message".[3]

● History of the workBeethoven conceived of the plan for his final three piano sonatas (Op. 109, 110 and 111) during the summer of 1820, while he worked on his Missa Solemnis. Although the work was only seriously outlined by 1819, the famous first theme of the allegro ed appassionato was found in a draft book dating from 1801–1802, contemporary to his Second Symphony.[7] Moreover, the study of these draft books implies that Beethoven initially had plans for a sonata in three movements, quite different from that which we know: it is only thereafter that the initial theme of the first movement became that of the String Quartet No. 13, and that what should have been used as the theme with the adagio—a slow melody in A-flat major—was abandoned. only the motif planned for the third movement, the famous theme mentioned above, was preserved to become that of the first movement.[8] The Arietta, too, offers a considerable amount of research on its themes; the drafts found for this movement seem to indicate that as the second movement took form, Beethoven gave up the idea of a third movement, the sonata finally appearing to him as ideal.[9]

● LegacyChopin greatly admired this sonata.[citation needed] In two of his works, the second piano sonata and the Revolutionary Etude, he alluded to the opening and ending of the sonata's first movement, respectively[10] (compare the opening bars of the two sonatas, and bars 77-81 of Chopin's Etude with bars 150-152 in the first movement of Beethoven's sonata). Prokofiev based the structure of his Symphony No. 2 on this sonata. In 2009, the Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero wrote a composition for piano solo entitled Op. 111 - Bagatella su Beethoven, which is a blend of themes from this sonata and Dmitri Shostakovich's musical monogram DSCH. The work is commemorated in chapter 8 of Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann. Kretschmar, the town organist and music teacher, delivers a lecture on the sonata to a bemused audience, in the fictional town of Kaisersachern on Saale, playing the piece on an old piano while declaiming his lecture over the music:

| ||

|

| ||

'Lecture Concert' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 해피크리스마스~* (0) | 2015.07.14 |

|---|---|

| 바흐 골드베르그 앙상블~ (0) | 2015.07.14 |

| 바흐 크로마틱 (0) | 2015.07.14 |

| 세기의 피아니스트 (0) | 2015.07.14 |

| 무소르그스키 <전람회의 그림> (0) | 2015.07.14 |